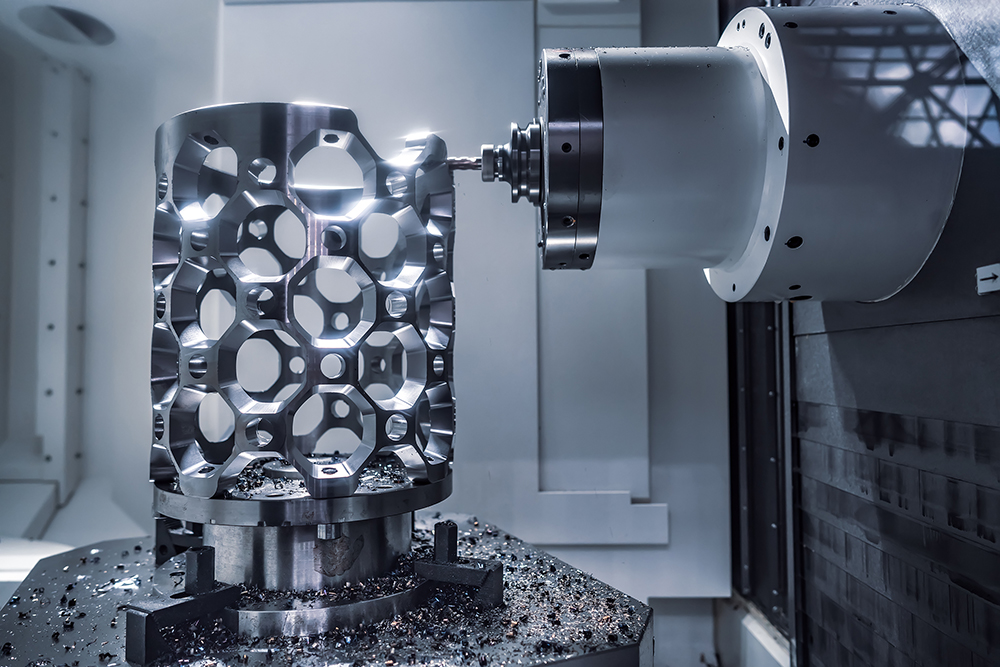

Worn-out industrial milling tools and damaged materials cost the manufacturing industry billions each year.

In manufacturing processes, components are shaped by removing chips from a bulk material, but a clear understanding of what factors control the size and shape of removed chips has remained elusive, limiting the manufacturing sector to incremental advancement based on trial-and-error approaches.

Making a perfect cut every time is desirable, and now researchers at Aarhus University have modelled and experimented their way to solve the long-standing challenge of finding a perfect cutting process that minimises tool wear and optimizes surface finish.

“We have developed a simple analytical model that can predict the mechanism for chip formation and its transition for almost every material. The model reveals the existence of a critical cutting depth as a function of material properties, tool geometry and running conditions,” says Associate Professor Ramin Aghababaei who’s leading the project at Aarhus University.

The study has been published in the scientific journal Physical Review Letters and the research is part of the project Cutting-Edge.

Ramin Aghababaei continues:

“By testing on various plastic materials, we have found a critical cutting depth, below which we can remove long chips in a smooth and gradual way and above which short and irregularly-shaped chips formed in an abrupt manner.”

The associate professor points out that deviation from this critical cutting depth has a major impact on wear and tear of the tools used, on energy consumption, and on the final product finish.

“We will continue to develop the model, but tool industries can start using it already to design optimal cutting tools,” he says.

The research forms part of the Grand Solutions project, Cutting-Edge, which aims to improve the performance of cutting tools for stainless steel processing. The project is funded by the Innovation Fund Denmark with 7 MDKK.

The publication is a result of a collaboration with Assistant Professor Mohammad Malekan from the University of Southern Denmark and Associate Professor Michal Budzik from Aarhus University.

There is an urgent need for the next generation of milling tools for manufacturing, because the useful lifetimes of today’s tools are too short and this is very costly for industrial enterprises.

For this reason, the Danish Advanced Manufacturing Research Center (DAMRC) is working with Danish and foreign universities and companies to maintain the competitiveness of Denmark.

“Denmark is very talented, but costs are high. If we are not constantly at the forefront, we will lose touch. That’s why it’s important that we work together across universities and industry to generate new knowledge on current issues, and to make sure that this knowledge is implemented in real life,” says Charlotte Frølund Ilvig, senior project manager at the DAMRC.

Throughout the world, machines, tools and software are being developed for machining metal, wood and plastics. For example, a lot of work is put into developing the next generation of efficient and durable milling tools by, among other things, developing surface coatings, adapting machining parameters and optimising tool geometry.

And this development is absolutely crucial, adds Torben Nielsen, CEO of TN Værktøjsslibning, a manufacturer of both special and standard tools for processing different materials.

“If the milling tool is not completely up-to-date, companies cannot use their machines properly. This means that they cannot optimise their production: they have too much consumption and too little productivity. If you don’t use your energies to develop these things, then you won’t be here in two years’ time. You’ll be out-competed. Major manufacturers around the world are moving fast, competition is brutal, and so it’s vital that we work together to keep Denmark competitive,” he says.

According to Charlotte Frølund Ilvig, many large Danish companies are already collaborating with universities and knowledge centres on developing new knowledge. However, there is still a large potential – especially amongst the small and medium sized companies (SMEs).

“But reality is beginning to raise its head. I feel that more and more companies are realising that they have to develop to keep up,” she says and continues:

“We need to do more projects like this and give SMEs a taste of how collaboration with knowledge institutions can pay off.”