New research can put an end to allergic reactions

Researchers have found a new mechanism in which an antibody can prevent allergic reactions in a broad range of patients. It is a scientific breakthrough, which could pave the way for a far more effective allergy medicine.

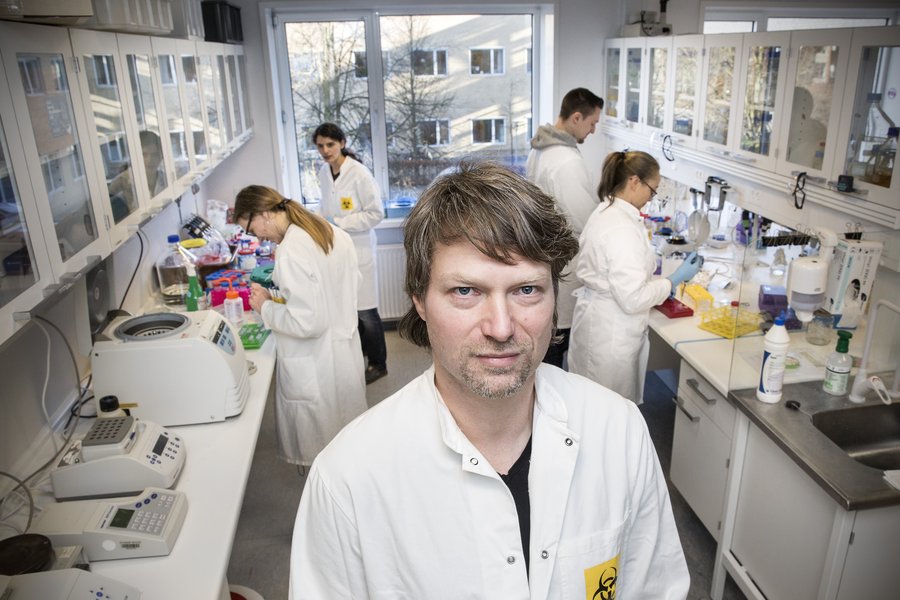

There was great excitement in the laboratory when researchers from Aarhus University recently discovered the unique mechanisms of an antibody that blocks the immune effect behind allergic reactions.

The team of researchers from the Departments of Engineering and Molecular Biology and Genetics together with German researchers from Marburg/Giessen has now described the molecular structure and mechanisms of action of the antibody, and the results are surprising.

They were hoping to find new methods to improve existing treatment, but instead they identified how a specific antibody is apparently able to completely inactivate the allergic processes.

The antibody interacts in a complex biochemical process in the human body by which it prevents the human allergy antibody (IgE) from attaching to cells, thus keeping all allergic symptoms from occurring.

“We can now describe the interaction of this antibody with its target and the conformational changes very accurately. This allows us to understand, how it interferes with the IgE and its specific receptors on the immune cells of the body, which are responsible for releasing histamine in an allergic reaction," says Edzard Spillner, associate professor at the Department of Engineering, Aarhus University.

The research results have now been published in the prestigious scientific journal Nature Communications.

Allergic effects of birch pollen and insect venom eliminated

Generally, an allergic person produces high levels of IgE molecules against external allergens when exposed to them. These molecules circulate in the blood and are loaded onto the effector cells of the immune system which triggers the production of histamine and thereby an immediate allergic reaction in the body.

The function of the antibody is that it interferes with binding of IgE to the two specific effector (CD23 and FceRI) on the immune cells, thereby making it impossible for the allergy molecule to bind.

Furthermore, the researchers have observed that the antibody also removes the IgE molecules even after binding to its receptors.

"Once the IgE on immune cells can be eliminated, it doesn’t matter that the body produces millions of allergen-specific IgE molecules. When we can remove the trigger, the allergic reaction and symptoms will not occur," says Edzard Spillner.

In the laboratory, it took only 15 minutes to disrupt the interaction between the allergy molecules and the immune cells.

The researchers have conducted ex vivo experiments with blood cells from patients allergic to birch pollen and insect venom. However, the method can be transferred to virtually all other allergies and asthma.

Hope for better medicine

Today, one in three Europeans suffer from allergic diseases, and the prevalence is steadily increasing. The treatment options are limited, but the researchers now expect that their scientific results will pave the way to developing completely new types of allergy medicine.

“We can now precisely map how the antibody prevents binding of IgE to its receptors. This allows us to envision completely new strategies for engineering medicine of the future, "says Nick Laursen, assistant professor at the Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics.

The antibody is particularly interesting because it is effective, and at the same time considerably smaller than therapeutic antibodies currently used to produce allergy medicine.

"It is a so called single domain antibody which easily produced in processes using only microorganisms. It is also extremely stable, and this provides new opportunities for how the antibody can be administered to patients,” says Edzard Spillner.

Unlike most therapeutic antibodies already available on the market, the new antibody does not necessarily have to be injected into the body. Because of its chemical structure it might be inhaled or swallowed, and these new consumption methods will make easy, cheap and much and more comfortable for the patients to handle.

However, before new allergy medicine can be produced the researchers will have to conduct a wide range of clinical trials to document the effect and safety of the antibody.

Contact

Associate Professor Edzards Spillner, Department of engineering, Aarhus University

Assistant Professor Nick Stub Laursen, Department of molecular biology and genetics