New researcher wants to develop cancer medicine in Denmark. She has a unique idea

Lili Zhang wants to use her knowledge about mechanical engineering to develop new types of cancer medicine. The idea is new, the approach is innovative and highly interdisciplinary, and just thinking about the potential clinical impact is enough to make you dizzy.

It makes Lili Zhang dizzy too.

She has come to Aarhus University to realise an idea that first came to her a year ago at a hospital in Shanghai.

The doctors were sorry. They couldn't cure her father of a rare and aggressive type of cancer, and they had given up on the costly treatment.

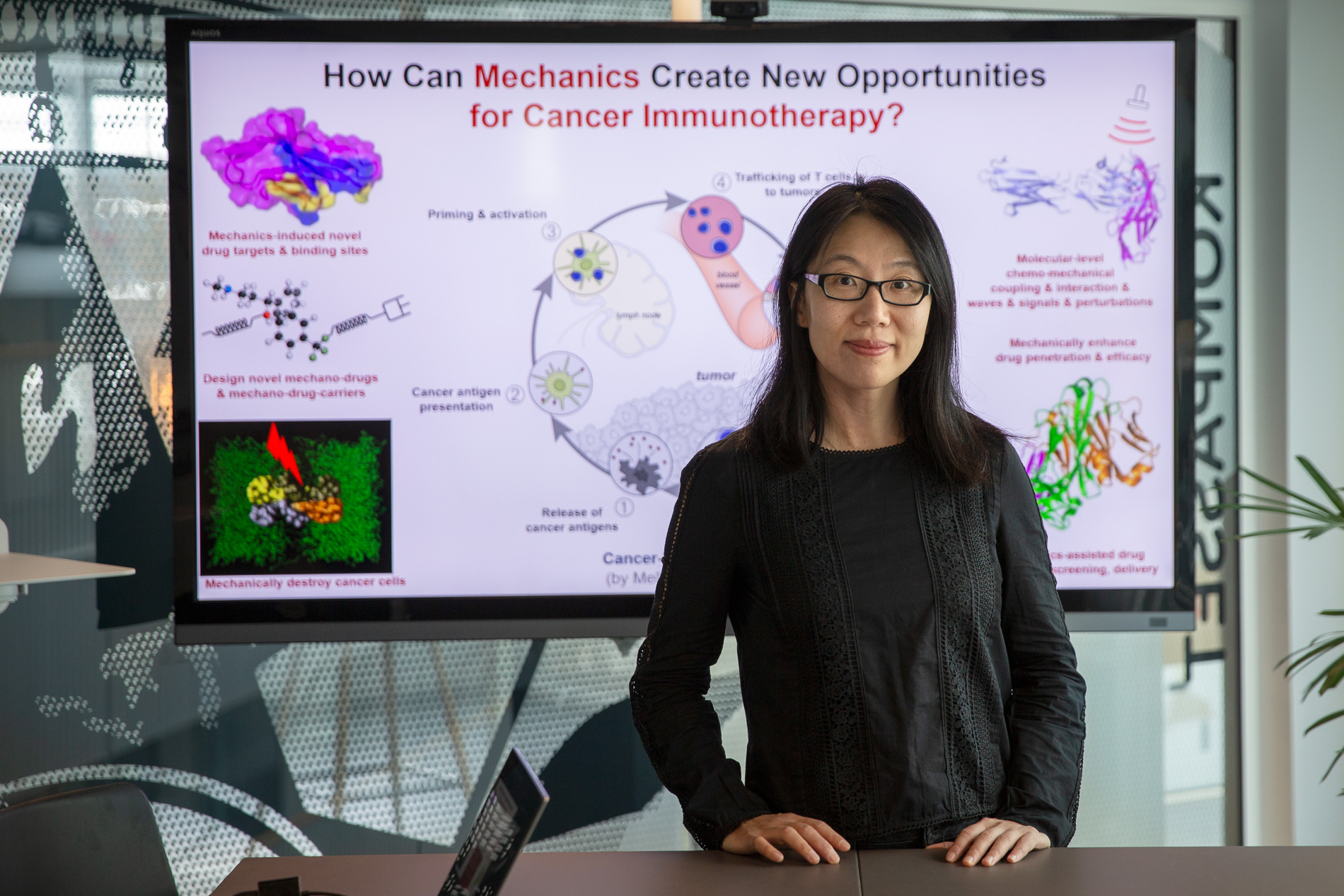

"It triggered a myriad of questions that the doctors couldn't answer, and I began to plough through huge amounts of scientific literature about cancer immunotherapy. With my engineering knowledge, I could see patterns from a multiscale mechanics perspective. I could understand how a drug works: how it ‘talks’ to its targeting molecule and responds to perturbations such as mutations and mechanical stimuli in its microenvironment. I could also see how a drug, when it doesn't work, could possibly be fixed by mechanical means, and how to trick it into functioning in new ways," says Lili Zhang.

She is well aware that her research is in the high-risk category, but she has strong personal conviction and commitment.

"I'm on my own here. No one else has gone this way before. But I believe my idea is worth pursuing. It may prove to give us a new understanding of cancer and cancer treatment at the molecular level, and it may just pave the way for mechanics-inspired design of new medicines," says Lili Zhang.

Read more about the Department of Mechanical and Production Engineering

Upside down

China’s Northeast features a terrain of fertile plains, rugged mountains, dense forests, and a wonderland of hardened lava, volcanic peaks and azure volcanic lakes. The Changbai Mountains extend from there across the border between China and North Korea. In the long, cold winters, the Songhua, Tumen, and Yalu Rivers freeze to ice, and there is a 7-month-long snowing period on the mountains.

Most of the children here dream of the great big world far away, and Lili Zhang grew up here in a hard-working Chinese middle-class family with a strong sense of unity and rich educational traditions.

She herself says that she has an innate curiosity, and that this paved the way for an unusual research career in mechanics.

"Be kind and hopeful, be forward-looking and open-minded, and be focused and resilient. Never take anything for granted. You have to see things from different perspectives, and sometimes you have to turn everything upside down. I think this is what I learned from my upbringing, and it’s the common thread through all my research," says Lili Zhang.

The mechanics of the brain

Lili Zhang has just arrived in Denmark after several academic appointments at some of the world's best universities – including Oxford and Cambridge. She has always been passionate about clinically motivated challenges at the interface between medicine, biology and mechanics, and she has spent most of her waking hours studying the brain to understand the mechanical issues in traumatic injuries and diseases at molecular level.

"I'm fascinated by the relationship between mechanics and neurology. For example, what happens mechanically to a neuron when we incur a head trauma, or when we get Alzheimer's disease? What happens to the mechanical properties of the components of a neuron? How does this affect the neuronal functions? By asking these questions, engineering can offer completely new perspectives in our understanding of the brain, and it can open up new multidisciplinary avenues for prevention and treatment," she says.

An urgent matter

Lili Zhang started as an assistant professor at the Department of Mechanical and Production Engineering on 1 May 2021. She considers this as a turning point, and she is now bringing her work on the brain to a close so that she can boost the development of more effective immunotherapy in cancer treatment.

"I can see that mechanics has an enticing, untapped potential in this context. It makes sense for me to invest my energies here, where I might be able to impact innumerable lives. My next step is to establish collaborations with the biomedical and clinical communities, and with the pharmaceutical industries, so that we can start synergising our theoretical and experimental efforts. My approach is new, but I’m convinced that it’s possible to enrich the existing immune-oncology armamentarium with novel mechanics-inspired drugs for greater anti-tumour efficacy and frequency of response, and with less occurrence of resistance and treatment-related adverse events," she says.

And for Lili Zhang the matter is urgent. At home in the north-eastern part of China, her father is still living with the incurable cancer that even the latest form of immunotherapy has not been able to deal with.

A new way of looking at the immune system

The immune system protects the body by fighting off invaders and aberrant cell growths like cancer. But cancer cells are tricky. They can masquerade as healthy cells to evade immune surveillance and detection. Cancer can also suppress and subvert the natural immune response by preventing our best weapon against cancer - tumor-specific T-cells - from doing their jobs. These mechanisms increase cancer’s ability to grow, metastasize, and resist traditional treatments.

Immunotherapy is considered to be one of the most promising strategies to treat cancer.

"It works by unleashing one’s own immune system to recognize, attack and kill cancer cells. The principle is that tumors express specific tumor antigens which are not expressed or expressed to a much lesser extend by healthy cells and hence can be used to initiate a cancer-specific immune response," says Lili Zhang.

Unfortunately, current forms of immunotherapy only benefit a small percentage of patients, and only a small subset of them truly achieves long-term survival outcomes. Moreover, the treatment comes with a risk of diverse and potentially serious immune-related adverse events.

Lili Zhang wants to try to change this:

"I think engineers can play a much bigger role in cancer research, because we can illuminate how mechanical forces, in concert with chemical and biological factors, sculpt cellular functions in health, disease, and treatment. I believe mechanics bring together cancer and the immune system in a completely new way. My idea is also to design nano-sized carriers that can protect the medicine, penetrate and release it very accurately deep into the tumour," she says.

Contact

Lili Zhang, Assistant Professor, the Department of Mechanical and Production Engineering