He builds satellites – when every boy’s dream comes true

After three days in the clean room, five Aarhus University students finished building the Delphini-1 satellite, which will be sent into orbit next year as part of the university’s space programme. One of the five is Kåre Jensen, who is busy studying engineering.

Space. The final frontier. How many hours have you spent gazing at the night sky and wondering? Dreaming of a journey between stars and galaxies?

The space industry – with NASA as a source of inspiration – has been a dream for many young people. However, it is a dream that is often shattered by reality in one way or another. You should be realistic, shouldn’t you? Or what? The childhood dream is still alive, and continues to be, for 25-year-old Kåre Jensen, who is studying for an MSc in Engineering at Aarhus University.

He is one of the five students who have now finished building Aarhus University’s first satellite – Delphini-1 – which is the backbone of the university’s AUSAT-1 space programme.

Read also: Aarhus University is getting its own space programme.

“Ever since I started upper secondary school, I’ve been fascinated by the entire space industry. I can remember one night in particular many years ago when I was sitting at the computer with a friend. His father suddenly burst in and said that the launch from Cape Canaveral was being streamed live. It was incredibly exciting to follow the launch, and that was kind of the start of my interest. I then started following Copenhagen Suborbitals, and SpaceX came later,” says Kåre Jensen.

His interest in space has made a deep impression ever since, which is why he has been waiting for a project like AUSAT-1 since commencing his engineering degree programme in ICT. The project is spread over several semesters and deals with space and the space industry.

“I’d really like to work on something like this in the future. And I think there are better opportunities nowadays because it’s really been a growing industry for many years as it’s become considerably cheaper to launch things in space,” he says.

(Article continues below the image)

Once construction of the satellite has been completed, it can be used to collect research data in space. Until then, it is a learning process for the professors, associate professors and students who are involved in the project at the university. Photo: Lars Kruse.

Kåre has always known that he wanted to be an engineer. Right back in his earliest years at school, he liked ‘solving problems’, as he puts it.

“I liked fixing people’s problems and finding better ways to do things. This is exactly what engineers do – they solve problems that can change the world. The hard part was deciding what sort of engineer I wanted to be,” he says.

The choice fell on the ICT programme, and working with electronics can only be said to run in the family. Kåre’s two elder brothers are both graduate engineers – one in information technology and the other in healthcare technology. And even though Kåre’s father is a doctor, he has always been an ‘engineer at heart’.

“My father started off as a radio mechanic during the heyday of Bang & Olufsen (B&O). He’s always been interested in technology, even though at some point he made a radical change to become a doctor. When my brothers were going to school, my home was the only one in the neighbourhood with a computer,” he says.

The world has changed dramatically since then. At that time, twenty-five years ago, Kåre and his family lived in Herning, and there was not a single shop in the town where you could buy a mouse for a computer. Aarhus University is now in the process of building a quantum computer in the basement and is about to send its first satellite into orbit. All of which is progress in the field that Kåre is specialising in.

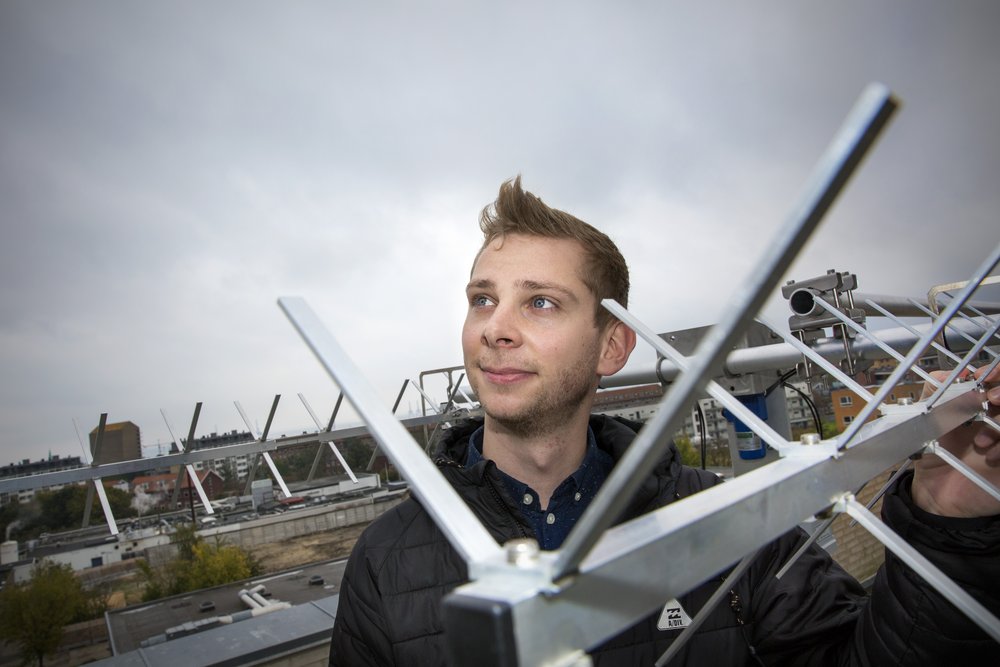

(Article continues below the image)

“I liked fixing people’s problems and finding better ways to do things,” says Kåre Jensen, an MSc in Engineering student. He is seen here at the antenna station – Ground Station – on the Edison Building, Aarhus University. Photo: Lars Kruse.

And there is a need for people like Kåre in the business sector. Not only in the space industry, but everywhere that smart products and big data are filling more and more in industries that were previously exposed to digitisation. Kåre also noticed this when he completed his BSc degree and prior to commencing the two-year period of advanced studies to complete his MSc.

“It was very tempting to go out and work at that time because all my year group were contacted by companies offering jobs. Of all those I know who stopped, there wasn’t a single one who hadn’t got a permanent job before they’d finished their Bachelor’s project. It feels really good, and it’s great to know that these opportunities exist. However, I’ve always known that I’d continue studying, and I’ve always had the attitude that I’ll work until I’m eighty anyway. So taking a couple of years more or less doesn’t mean the world,” says Kåre.

In the coming years, Kåre can look forward to many interesting hours working with space technology. Now that both the satellite and the base station to control it have been finished, there will be countless test runs, and some of the students will be going to NASA in Houston prior to launching the satellite. And after that … well, the sky is not really the limit any more.

Facts about Delphini-1

- The satellite will be sent to the International Space Station (ISS) from a launch site in Houston in June or July. ISS will then send it further into space when it fits in with their remaining programme.

- The hardware components of the satellite cost approximately EUR 60,000 (about DKK 446,000). The control station for the satellite cost approximately EUR 30,000 (about DKK 223,000).

- The satellite components were purchased by GomSpace, the Danish company that designs nano-satellites.

- The overall budget for the project is EUR 200,000 (about DKK 1.5 million).

- Five students are attached to the project. Out of 22 applicants, 15 were chosen for the first workshop, and they drew lots to see who would be granted permission to assemble the satellite.

- The five students come from the Department of Physics and Astronomy, the Department of Geoscience, and AU Engineering.

- The satellite is equipped with a battery maintained by solar cells mounted on the sides.

- The length of time the satellite is in orbit depends on the solar activity affecting the atmosphere. This is expected to be 4–6 months according to Assistant Professor Victoria Antoci, who is the project manager. If the prognoses prove correct, however, and the solar activity is low, it could possibly remain in orbit for a year.